Decoding Car Repair Costs: How Much Will It Really Cost to Fix My Car?

It’s a question every car owner dreads: “How much will this car repair cost me?” Whether it’s a mysterious noise, a blinking dashboard light, or something more serious, understanding the costs involved in car repairs can feel like navigating a minefield. Initially, when thinking about car troubles, many people look for simple rules, like the 50% Rule, hoping for a straightforward answer to the “repair or replace” dilemma. This rule suggests comparing repair costs to a threshold—often 50% of the vehicle’s value or replacement cost—to decide whether to fix or scrap a car.

However, the reality of car repair costs is far more complex than any single rule can capture. As someone deeply involved in automotive diagnostics and repair at CARDIAGTECH, I’ve learned that determining the true cost of fixing your car requires a deeper dive than just a quick calculation. The need your car fulfills, your budget, and the overall condition of your vehicle all play crucial roles in deciding whether a repair is economically sound.

Both repairing and replacing your car come with their own sets of advantages and disadvantages. The decision often hinges on a variety of factors that a simple formula struggles to encompass. Can a generic rule truly account for all the nuances and provide the right answer for every car owner? While rules like the 50% Rule might seem appealing for their simplicity, they often fall short when it comes to real-world car repair decisions.

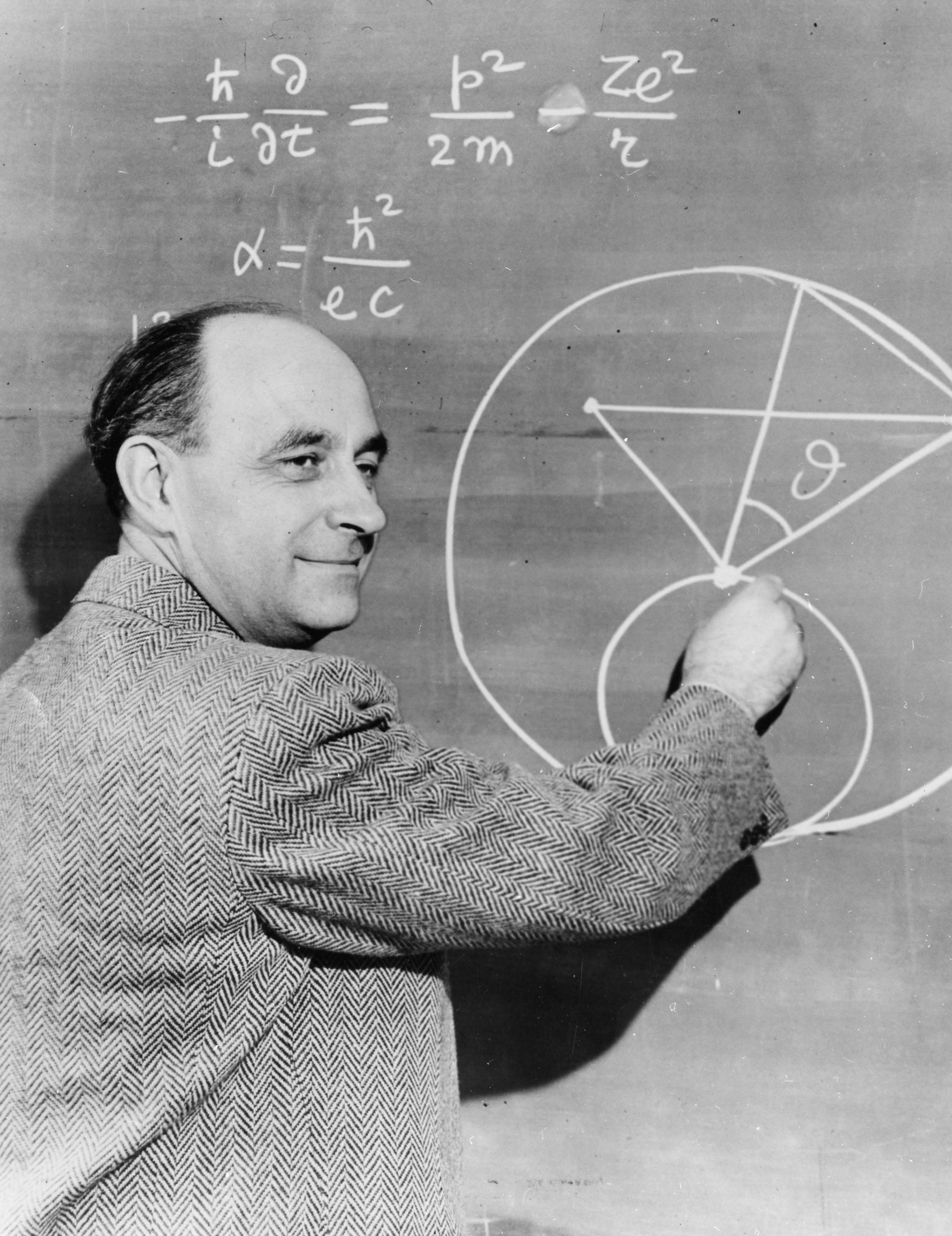

Italian-born physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-1954) at the chalkboard

Italian-born physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-1954) at the chalkboard

Understanding the complexities of car repair costs is more intricate than a simple equation.

The Lingering Value of Your Broken-Down Car

Before we delve into estimating repair costs, it’s crucial to recognize that even a broken car isn’t entirely worthless. Even in a non-running condition, your vehicle still holds some value, known as its salvage value. This is the amount you can potentially get if you decide against repairs and opt to sell your car as-is. In the automotive context, salvage value is what junkyards or parts recyclers might offer for your vehicle, even if it’s severely damaged.

Salvage values fluctuate widely based on factors like vehicle type, age, condition, and the demand for parts. A newer car with damage might have a higher salvage value due to valuable components, while an older, heavily worn vehicle might have minimal salvage value. In some cases, particularly with very old or severely damaged cars, the salvage value can even be negative if disposal fees exceed the scrap value of the materials. It’s always wise to get a salvage quote before making a repair decision, as this can offset the cost of a new vehicle or influence your repair budget.

Scarcity and demand significantly impact salvage value, especially for classic or rare cars. For instance, a vintage muscle car, even in disrepair, can fetch a high salvage price due to demand from restorers and collectors. Conversely, common, older models might have very low salvage values. In extreme cases, like a car encrusted with precious metals, the functional state becomes almost irrelevant to its salvage value.

The Added Value of Car Repair: Is It Worth It?

While a breakdown diminishes your car’s value, a successful repair should theoretically restore or even enhance it. However, recouping the full repair investment when you decide to sell isn’t always guaranteed. The market dictates resale value, and buyers are primarily concerned with the current market price, not your past repair expenditures.

Consider this scenario: you buy an older car for $1000. After some months, the transmission fails. A mechanic quotes $3000 for a replacement. You proceed with the repair, thinking the car will now be worth at least $4000. However, a year later, when you try to sell, similar cars are still selling for around $1000-$1500. What happened to your $3000 investment?

(image: hobvias sudoneighm / CC BY 2.0)

Just like the Millennium Falcon, your car’s true value isn’t always reflected in its appearance or repair history.

The car market is competitive. Potential buyers are comparing your car to all other available options at that moment. They’re not necessarily willing to pay extra just because you recently replaced the transmission. Your $3000 repair essentially brought your car back to par with other vehicles in the $1000-$1500 price range. While it now has a new transmission, a potential buyer could opt for a cheaper, similar car and still get reasonable transportation.

This illustrates that the market limits how much of your repair costs you can recover upon resale. Let’s quantify this “value-added” by repair.

- Msalvage = Market salvage value of the broken car.

- Mpost-repair = Market value of the car after repair.

- Rvalue-added = Value added by the repair.

The relationship is: Mpost-repair – Msalvage = Rvalue-added

In our transmission example, if the salvage value was $200 and the resale value after the $3000 repair is $1200, then:

$1200 – $200 = $1000

The market values the transmission repair at $1000, even though you spent $3000.

To avoid financial loss, the repair cost (Rcost) should ideally be less than or equal to the value added:

Rcost ≤ Rvalue-added

In our scenario, $3000 (repair cost) is NOT less than or equal to $1000 (value-added), resulting in a financial loss. The profit or loss from repair is:

Rvalue-added – Rcost = Rprofit/loss

$1000 – $3000 = -$2000

A $2000 loss on the transmission repair. However, if a skilled mechanic could fix it for $500, the calculation becomes:

$1000 – $500 = $500

A $500 profit in terms of market value increase compared to repair cost.

Where Does Your Repair Money Actually Go?

The risk of not recouping repair investments is common, not just in cars, but in home renovations and other asset improvements. When you repair with the intent to resell, you’re essentially acting as a manufacturer, taking a broken item, investing in parts and labor, and creating a “repaired” product for the market.

In the car repair example, you’re taking a damaged car, adding a new transmission and mechanic labor, and creating a car with a new transmission but still an old car. The question is: does the market want this product at a price that justifies your investment? In our example, the answer is no. Buyers of used cars in that price range aren’t necessarily looking for new transmissions; they’re seeking affordable transportation.

However, if you intend to keep the car and drive it for many more years, the market resale value becomes less critical. The repair is then for your personal use and value. The decision becomes based on your personal needs and how much you value having a working car versus the cost of repair.

Even then, opportunity cost remains. The $3000 spent on the transmission could have been used differently. Selling the car for salvage ($200) plus using savings ($1300) to buy another used car for $1500 might have solved the transportation need, leaving $1500 available for other uses. Every repair decision involves weighing opportunity costs – what else could you do with that money?

The Flawed 50% Rule and Car Repairs

Now, let’s revisit the 50% Rule in the context of car repairs. The rule generally states: if repair costs exceed 50% of a certain benchmark, replace; otherwise, repair. The inequality favoring repair is:

Repair Cost < 50% of Benchmark Value

The problem is, the “benchmark value” is vaguely defined and often cited as:

- Original purchase price of the car.

- Current replacement value of a similar used car.

- Cost of a new car.

Each benchmark leads to vastly different conclusions, making the 50% Rule unreliable for car repair decisions.

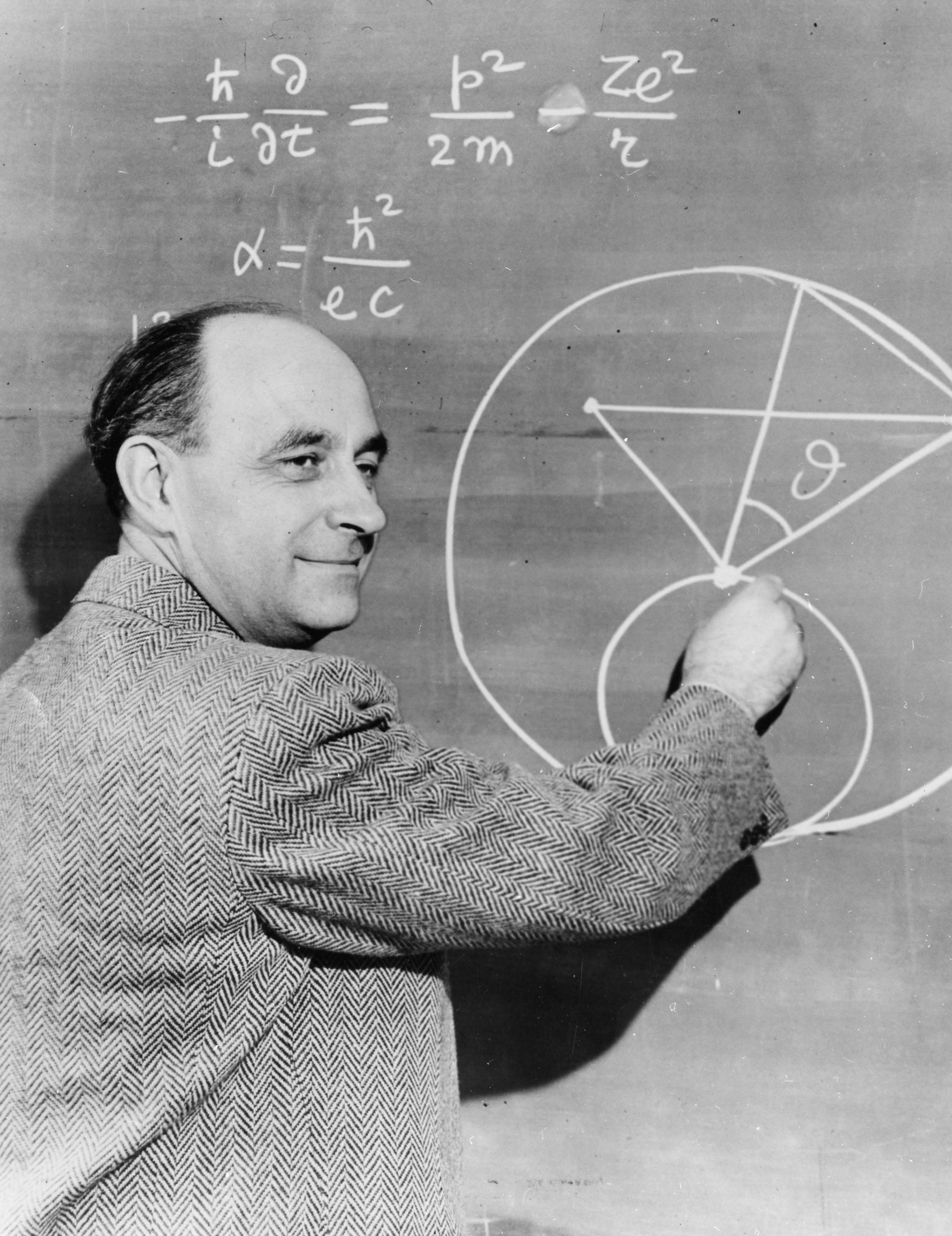

Left side of ENIAC as installed in BRL Bldg 328 (US Army Photo, from the archives of the ARL Technical Library)

Left side of ENIAC as installed in BRL Bldg 328 (US Army Photo, from the archives of the ARL Technical Library)

Using the original purchase price as a benchmark for car repair decisions is often misleading due to inflation and depreciation.

Original Price: An Irrelevant Benchmark for Car Repair Costs

Using the original purchase price for the 50% Rule is particularly flawed for cars. Cars depreciate significantly over time. Inflation further distorts the original price’s relevance. Using the original price as a benchmark would consistently suggest repairs, even for very old cars, simply because the repair cost is unlikely to exceed 50% of the original (higher) price. This benchmark ignores the car’s current depreciated value and the reality of car repair expenses in today’s market.

Furthermore, technological advancements in the automotive industry make older cars less desirable and less valuable compared to newer, more efficient, and safer models. Basing repair decisions on the original price of an outdated vehicle makes little economic sense.

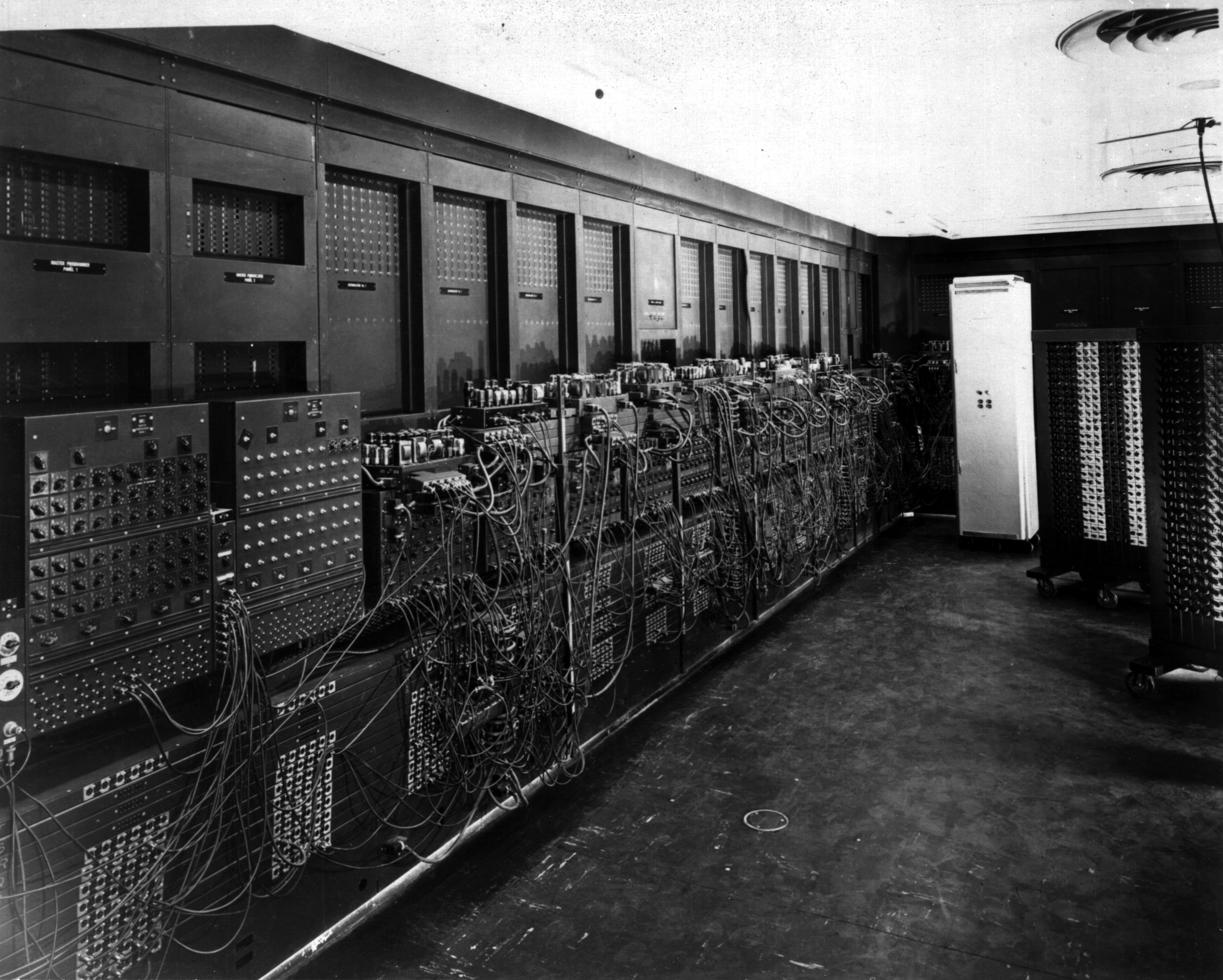

US Army Photo (163-12-62) Patsy Simmers, Gail Taylor, Milly Beck, and Norma Stec with parts from ENIAC, EDVAC, ORDVAC, and BRLESC-I

US Army Photo (163-12-62) Patsy Simmers, Gail Taylor, Milly Beck, and Norma Stec with parts from ENIAC, EDVAC, ORDVAC, and BRLESC-I

Technological advancements render older car components less relevant, making replacement cost of similar used parts a more practical benchmark.

Replacement Cost of a Similar Used Car: Still Problematic

Using the replacement cost of a similar used car as a benchmark seems more logical at first. It attempts an “apples-to-apples” comparison: “How much would it cost to replace my broken car with a working one of similar age and condition?” This benchmark avoids the distortions of inflation and original price.

However, practical issues remain:

- Finding an “identical” replacement is often impossible. Cars are unique. Mileage, maintenance history, and condition vary greatly even within the same make and model year. Finding a truly “identical” replacement for pricing comparison is unrealistic.

- Used car market pricing is volatile and location-dependent. Used car prices fluctuate based on region, demand, and availability. Online price guides provide estimates, but actual market prices can vary.

- Condition is subjective and difficult to assess. Two cars of the same year and model might have vastly different mechanical conditions. A lower price might reflect hidden problems.

While better than original price, used replacement cost is still an imperfect and often impractical benchmark for car repair decisions.

New Car Cost: Comparing Apples to Oranges

Using the cost of a new car as the benchmark for the 50% Rule is even more flawed when considering car repairs. It compares the repair cost of an old, used car to the price of a brand-new vehicle.

Consider our $3000 transmission repair on an older car. A comparable new car might cost $30,000. Applying the 50% Rule:

$3000 (Repair Cost) ÷ $30,000 (New Car Cost) = 10%

The 50% Rule would strongly recommend repair since 10% is far less than 50%. However, this is nonsensical. Why would you spend $3000 on repairing an old car when its market value might only increase by $1000 (as in our earlier example), just because it’s far less than the price of a new car?

Comparing repair costs to the price of a new car is fundamentally flawed. A new car offers benefits an old, repaired car cannot: new warranties, modern features, better fuel efficiency, and updated safety technology. The 50% Rule using a new car price as a benchmark completely ignores these crucial differences.

Rethinking Car Repair Costs: Focus on Value, Not Rules

The 50% Rule, regardless of the benchmark used, is not a reliable tool for making informed car repair decisions. It oversimplifies a complex economic and practical problem.

A more sensible approach is to focus on the value-added repair model:

Rvalue-added – Rcost = Rprofit/loss

This model compels you to estimate the market value of your car after repair (Mpost-repair). This requires considering the current used car market and what similar vehicles are selling for. It forces a realistic assessment of whether the repair investment will be reflected in the car’s value.

Beyond numbers, consider your needs and priorities. Has your transportation requirement changed? Does the car still meet your needs even if repaired? Could a different car (new or used) better serve you now? Sometimes, a breakdown is an opportunity to reassess your car ownership and consider upgrading, downgrading, or even eliminating a vehicle if your needs have evolved.

Perhaps you’ve realized you no longer need a large SUV and could manage with a more fuel-efficient sedan, or maybe public transport or ride-sharing has become a viable alternative. In such cases, selling your car for salvage and re-evaluating your transportation needs might be a more financially sound and lifestyle-enhancing decision than blindly following a repair rule.

Ultimately, deciding “how much to spend to fix my car” is a personal financial decision. It requires careful consideration of repair costs, vehicle value, market conditions, your transportation needs, and opportunity costs. Ditch the simplistic 50% Rule and embrace a more holistic and value-driven approach to car repair decisions.

What’s Your Experience?

Have you used the 50% Rule or a similar guideline for car repair decisions? What factors do you consider when deciding whether to repair or replace your vehicle? Share your experiences and insights in the comments below!

References:

Repair Or Replace? – Art of Troubleshooting

The Economics Of Troubleshooting – Art of Troubleshooting

Repair or Replace? – The New York Times

Repair or Replace? | AARP

Repair or Replace It? – Consumer Reports

Salvage Value Definition – Investopedia

Plymouth Superbird – Wikipedia

Tata’s £2.8m gold-coated Nano – Top Gear

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977) – Quotes – IMDb

hobvias sudoneighm – Flickr

Creative Commons — Attribution 2.0 Generic — CC BY 2.0

Car Talk – Wikipedia

Subjective theory of value – WikiMises

I, Pencil – Foundation for Economic Education

Intermediate good – Wikipedia

Subjective Value Theory – Mises Institute

9524.4 Repair vs Replacement of Facility Under 44 CFR SS206.226(f) 50% Rule | FEMA.gov

Constant dollars – Wikipedia

CPI Inflation Calculator

What You Should Know About Inflation – Ludwig von Mises Institute

ENIAC – Wikipedia

Moore’s law – Wikipedia

US Army Photo – Flickr

Royal Enfield Bullet – Wikipedia

Opportunity Cost – Art of Troubleshooting

BRLESC – Wikipedia

Chapter 5 – Ballistic Research Laboratories Report No. 1115

Lemon (automobile) – Wikipedia

Garbage in, garbage out – Wikipedia

Share this:

Like Loading…